Anas al Khabour, an international scholar and previous Director of the National Museum of Raqqa, has extensive hands-on experience theoretically and practically within Archaeology and museum operation. His area of expertise is Ancient Mesopotamia and, increasingly, the illegal trafficking of antiquities. In this interview, he talks about his background, a general overview of Mesopotamia and the Jazira region of Syria, the difficulties of archaeology in deciphering intangible heritage and the impact of illegal antiquities trafficking.

Could you give us a background on Mesopotamia and the Jazira region? it’s important to have some background on the subject before we discuss intangible heritage.

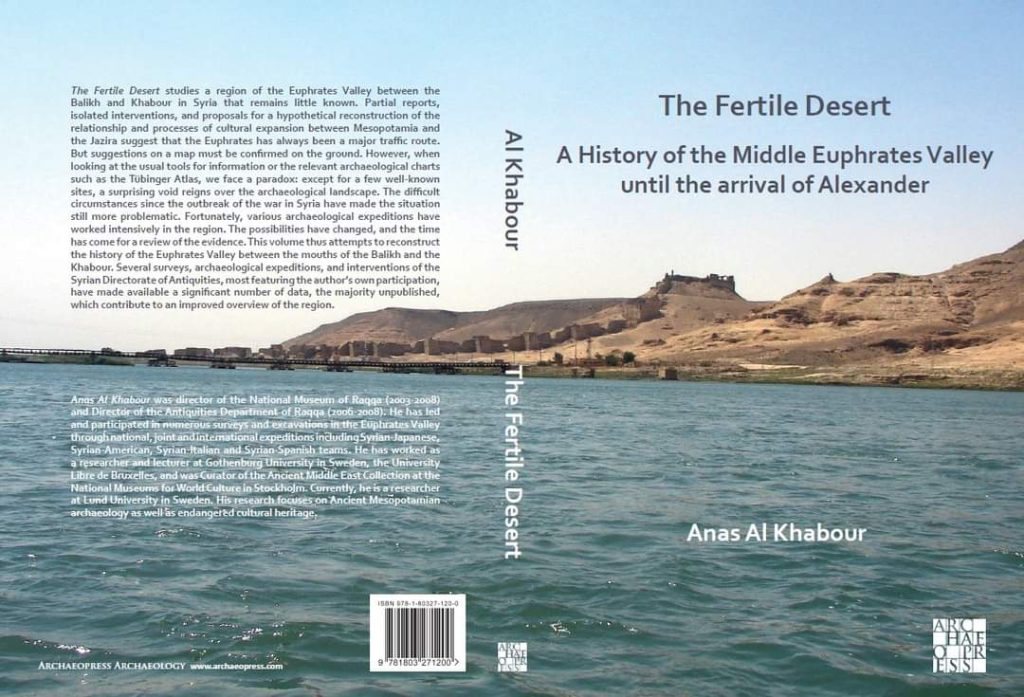

My research focuses on immovable heritage, religion and museums. I have worked in this area for many years since studying archaeology at the University of Damascus. I was the Director of Museums for Raqqa for about 5-6 years and have been involved in lots of archaeological excavations. Mesopotamia is my favourite topic, specifically the Bronze Age period of the 3rd to 2nd millennium BCE.

It seems to me that Mesopotamia and the Jazira region are full of different cultures and ethnicities that came together. This is especially true for cities like Raqqa in the more modern era even though there were large amounts of time when it wasn’t inhabited. Was this also true in the time period you focus on?

Yes, Raqqa is a very good example generally, especially after the Mongol Empire period of its history. After their invasion, there were six centuries when Raqqa wasn’t inhabited until the Ottoman Empire decided to establish cities in the surrounding regions and encouraged people to live there. In 1863 the Ottoman Empire built a police station in Raqqa to make people, travelling from all areas, feel safe enough to stay and work. After that, the modern city of Raqqa really started. Similar things could be seen across Jazira and the movement and settling down of people exists throughout the eras. The same is true of the Bronze Age period I focus on as people settled for great or important events.

Did the cultures of the new settlers in Mesopotamia and the Jazira region take over the pre-existing one?

That is an interesting question and we honestly don’t know for sure. In the scholarship, there is an ongoing debate on whether there was just a movement of people or a movement of ideas as well.

One challenge in archaeology is that only artefacts which can endure over time can be studied. Does this create an issue for exploring the intangible culture of these regions given that it tends to be recorded in different ways?

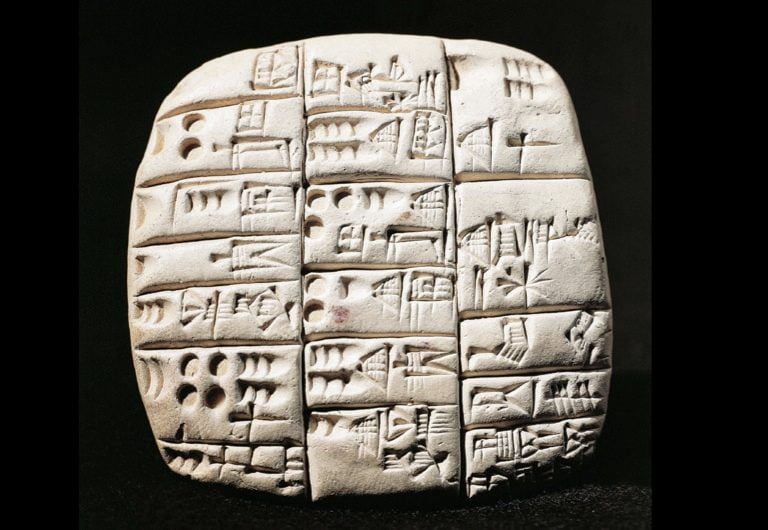

That is very true. A lot of the material, like cuneiform scripts (the earliest form of writing) and records, usually deals with the high classes of the time. Whereas, other data and findings, like the normal production of tools, are more useful for understanding the lower classes. I faced this problem of artefact degradation myself in my excavations in the Euphrates Valley. It was the role of the creators of Syrian museums to put these objects in their specific histories.

Speaking of the museums, why was the Department of Antiquities and Museums of Raqqa created in 1974?

Many excavations had been happening in the region. Officially, it mainly started in 1905 with the Ottoman Empire authorising the first excavation with the next one being in 1908. After the English translation of The Thousand and One Nights in the late 1800s, there started to be a massive interest in Raqqa. This was because the provenance of the author was Raqqa itself. The removal of bricks from heritage sites, already started previously, got worse as more people flocked to the city. The West also wanted to take objects with them as well. This forced the Ottoman Empire to enact their own archaeological digs which led to museums because of the sheer amount of things uncovered. In 1961 Raqqa was also named a Province and so this was part of a move to more firmly establish it.

As an academic living outside of Syria, it must be challenging to have a hands-on approach, especially with the rise of illegal antiquity trafficking. Your recent book, “The Illicit Trafficking of Cultural Properties in Arab States,” brings attention to this issue. right?

True, Illegal antiquity trafficking is a major problem in general. The documentation of museum items makes it easier to trace them if they are ever stolen and sold on the black market. The main problem is with illegal digging and looting because we don’t know what artefacts are actually being taken. When we find them, we also find it very difficult to tell where they originally were.

Experts and law enforcement agencies often overlook the critical issue of illegal antiquities. Despite the challenges that it comes with it, it is crucial to preserve the heritage of Mesopotamia and the Jazira region through the protection of these artefacts.

You are right although some bodies exist like a specialised law enforcement department in Italy to look into heritage crimes there. But, it is a serious issue and different artefacts present different challenges. Whether that be the archaeological context (where the item was found), its authenticity in a world of forgeries or some other problem. We used GIS to look at modern Syrian looted sites too and we found that all occupiers have been complicit in illegal lootings. While the legal framework varies in strength between countries, Syria is generally okay.