On setting a date for my 2018 summer wedding, I wanted to epitomise the traditional Damascene bride beside the Turkish knight of my dreams. My foot had not set on Damascus soil since the winter of 2013.

I planned small details to alleviate the heaviness of the absence of my mother and father from my wedding. I wanted to be happy. I hired a Damascene folklore group to sing in Arabic and Turkish, and a reserved a table at a Shami restaurant. In respects to my dress, I wanted it to include a piece from Damascus and thus began the adventurous trip of purchasing a meter of brocade, from the famous bazaars of Al Hamidiyah in Damascus to Istanbul, where I reside today.

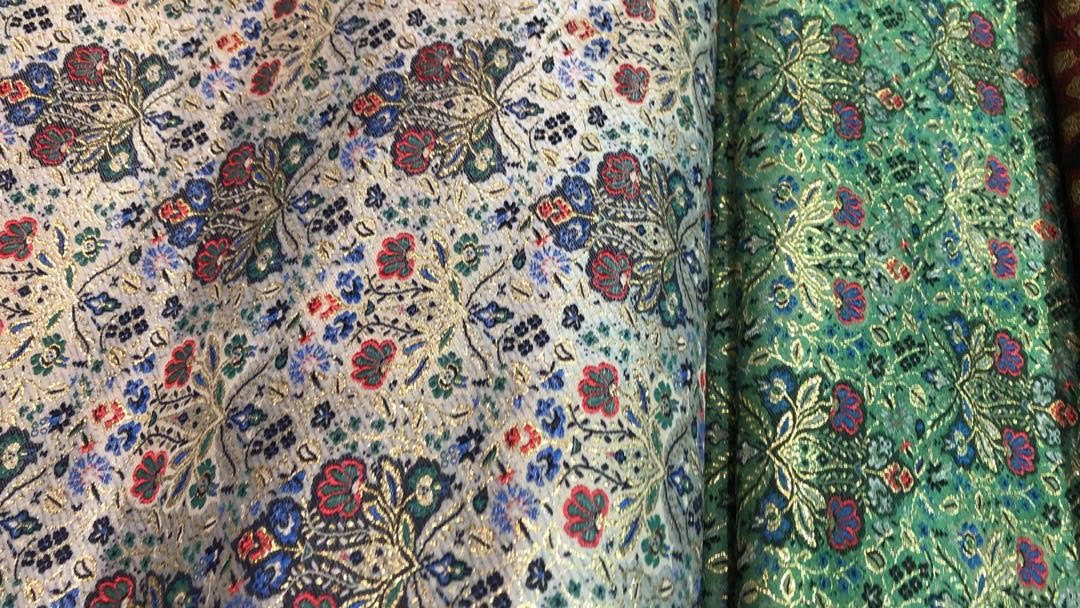

For those who do not know the story of brocade, I will relay it to you.

It is said that there was a Damascene cloth merchant called Ibraheem. And that it was he that mastered the marriage of silk thread with gold and silver. Creating a combination so beautiful it was worthy of Kings and Queens. One of his titles in colloquial Syrian was ‘bro’ combined with ‘kar’ (meaning profession), hence the cloth was named ‘brocar (brocarde)’.

My mother did not delay in sending me the most beautiful piece of white brocade from Damascus to Beirut, with a taxi driver she used to travel with. For several weeks, I awaited its arrival to a Lebanese courier office. This reason being the delay of my wedding on more than one occasion, as the material was destined for my veil. During the waiting period, my Syrian seamstress Oum Ayman left for Europe via the sea. Leaving me with no knowledge of a tailor or seamstress that had experience of working with brocade. Everything seemed to be going wrong! Yet we came across a kind man, who agreed to take my veil to Istanbul.

Alas my marriage took place without a wedding, and my veil remained melancholy and in the solitary confinement of my wardrobe. A cloth that was destined to sit upon the crown of a bride, found herself removed from her city, discarded between unfamiliar cloths that matched her neither in attribution, value or authenticity.

An old story and a photograph of Queen Elizabeth II in her wedding dress made from damascene brocade, appeared on Facebook.

I read the details of the story ‘The Queen’s Dress’, even though I had heard it several times from my mother and grandmother. In 1947, the British Royal Palace made a request to the Syrian Embassy in London, during the presidency of Shukri Al Quwatli. Requesting brocade for the royal wedding dress. Syria sent the palace a piece, its pattern being called ‘The Birds of Paradise’; the wings were embroidered with 10 karat gold. After the designer Norman Hartnell made the wedding dress, the pattern ‘Birds of Paradise’ became known as ‘The Queens’ pattern.

The story spurred me to release my veil that was prisoner to my wardrobe. I transformed her into a dress that did not fail to impress all eyes that fell upon her. I ordered more brocade from Damascus, accumulating it became a hobby of mine. My wardrobe slowly began to over-spill with garments made of brocade. I began to feel at peace every time I saw my very first piece, because now she was no longer in isolation, as this hobby soon evolved into my profession.